Like a Rainbow on the Stage

Sreevalsan Thiyyadi

August 13, 2012

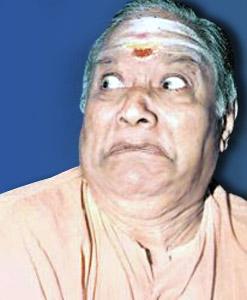

The consistent recurrence of the tragedy has tormented the Brahmin beyond consolation. Every time his wife delivered, the child would be stillborn. This was the ninth time he was appearing with the dead infant at Krishna’s durbar for relief. And the famously kind lord was yet again apathetic. The attitude triggers a range of emotions within the priestly-caste protagonist. He feels enraged, aggrieved, hapless, insulted and intrigued — all at the same time. To package this spectrum of emotions isn’t easy, more so in Kathakali which is a classical dance-drama steeped in stock movements and stylised acting.

But a maestro is one who isn’t bogged by the basic rules of his art, instead he takes them for springheads; even throws them to the wind occasionally. So Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair, as always, presented this segment of the play with characteristic gay abandon. His frenzied Brahmin would one night pace up to an edge of the stage and lean his forehead against the bamboo-pole propping its roof — and the audience would at that moment feel that the vertical beam was a golden pillar in the king’s palace, which is the venue of the mythological scene.

Now, dissect this bit of instant improvisation, and you notice at least two elements in it. One, the liberal use of space: the temerity to move farthest from the centre stage when Kathakali dictates minimal use of turf. Two, a touch of realism: the cleverness to cap that brief adventure trip with giving a feel of naturalness to what isn’t even theatre property: a grimy wooden mast.

Let’s not go deeper into this. For, Krishnan Nair’s masterpiece roles were after all the romantic heroes in Kathakali. The chequered-life Nala, ladies’ man Arjuna, a caught-in-the-middle Rukmangada, Bhima on a trek to bring scented Sougandhika flowers for his wife, Karna with his set of existential pangs…So, if he could leave a personal stamp on a temperamental and part-comical figure like the Brahmin, it was only because of his versatility — a penchant for giving individuality to even cameo characters in the vast repertoire of stories in the four-century-old ballet.

It is legendary that his antiheroes like Ravana and Duryodhana were a mix of pompousness and cunning, while his red-beard Bali revelled in crude wit and cocky body language. And his depiction of demonesses like Nakratundi and Simhika were as weirdly funny as were his graceful essaying of other female characters ranging from young Pootana-in-disguise to venerable Kunthi.

Yet, even in the peak of his glory — which lasted an incredibly long five decades — Krishnan Nair (1914-90) wasn’t free from criticism. In fact, within core circles, the brickbats somewhat outweighed the bouquets, given that the disapproving remarks came largely from scholars and connoisseurs. Krishnan Nair, in his know-it-all style, paid them scant attention and seldom seemed to believe that Kathakali is only for the class art-lover. As fame caught on, his choreography lost a certain crispness that pained his ageing methodist guru Pattikkamthodi Ravunni Menon (1881-1949) who refined the Kalluvazhi style of Kathakali currently being taught in Kalamandalam, where Krishnan Nair was an early-batch student.

The aesthetes from Pattikkamthodi’s central Kerala often felt indignant about the “wayward” strides on stage by North Malabar-born Krishnan Nair, who apparently trod such paths in a bid to woo the masses that his art form was losing to mainstream Malayalam cinema in the 1970s and a general alacrity those days to dub Kathakali as anachronistic. His practice of dictating rates for performances was considered outlandish by the average organisers, who were quick to call him haughty and money-minded. Nothing changed Krishnan Nair, and he ruled the roost all his life.

After his death, a major churning is taking place in the tastes of Kathakali buffs. Even those in downstate Travancore, who stood foremost in celebrating Krishnan Nair’s sublime histrionics and cheap antics, now seem to be settling for the ‘clean choreography’ theory. After all, there aren’t many around with a prowess to emote in a way that is remotely reminiscent of Krishnan Nair, so at least there be tidy dancing — this appears to be the mindset.

In short, Kathakali is giving up its stress on facial bhavas even while it is struggling to regain its jerk-less movements. The resultant predictability can make the art-form stale — unless and until it conjures up another Krishnan Nair of sorts in the future.

(The article was published in the 2010 August 29 Sunday magazine of The New Indian Express on the occasion of the 20th death anniversary of Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair.)